Gastro esophageal Reflux Disease

Gastro esophageal Reflux Disease

Prof. Dr. Mohamed Kamel Sabry

Prof. , Head of Dep. of Internal Medicine & Immunology

Ain-Shams Univercity

General Considerations

A. Incompetent Lower Esophageal Sphincter

B. Hiatal Hernia

C. Irritant Effects Of Refluxate

D. Abnormal Esophageal Clearance

E. Delayed Gastric Emptying

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms And Signs

B. Special Examinations

1. Upper Endoscopy

2. Barium Esophagography

3. Ambulatory Esophageal Ph Monitoring

Differential Diagnosis

Complications

A. Brrett`S Esophagus

B. Peptic Stricture

Treatment

B. Surgical Treatment

C. Endoscopic Therapy

General Considerations

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease affects 20% of adults, who report at least weekly episodes of heartburn, and up to 10% complain of daily symptoms. Though most patients have mild disease, up to 50% develop esophageal mucosal damage (reflux esophagitis) and a few develop more serious complications. Several factors may contribute to gastroesophageal reflux disease.

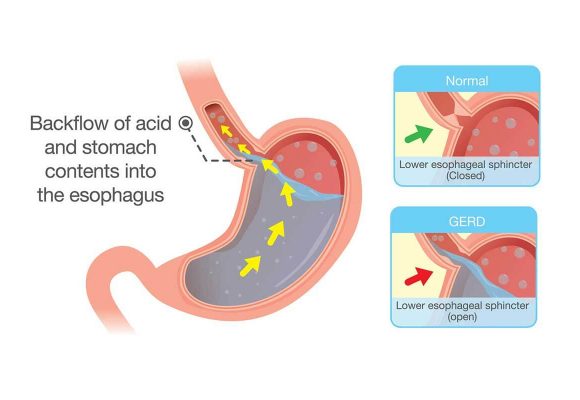

A. INCOMPETENT LOWER ESOPHAGEAL SPHINCTER

The antireflux barrier at the gastroesophageal junction is dependent upon intrinsic lower esophageal sphincter pressure, the intra-abdominal location of the sphincter, and the extrinsic compression of the sphincter by the crural diaphragm. In most patients, baseline lower esophageal sphincter pressures are normal (10 - 30mm Hg) . In patients without hiatal hernias, about 70% of reflux episodes occur during relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter that occur spontaneously (transient relaxations or as prolonged relaxation after swallowing . The remaining events occur during periods of low sphincter pressure ( hypotensive sphincter). A small number of patients with more severe involvement (especially those with strictures) have chronically incompetent sphincters(< 10 mm Hg), resulting in free reflux or stress reflux during lifting bending, or abdominal straining.

B. HIATAL HERNIA

Hiatal hernias are common and usually cause no symptoms. In patients with gastroesophageal reflux however, they are associated with higher amounts of acid reflux and delayed esophageal acid clearance leading to more severe esophagitis, especially Barrett,s esophagus. Increased reflux episodes occur during normal swallowing induced relaxation, periods of sphincter hypotension, and straining due to reflux of acid from the Hiatal hernia sac into the esophagus.

C. IRRITANT EFFECTS OF REFLUXATE

Esophageal mucosal damage is related to the potency of the refluxate and the amount of time it is in contact with the mucosa. Acidic gastric fluid (pH < 4.0) is extremely caustic to the esophageal mucosa and is the major injurious agent in the majority of cases. In some patients, reflux of bile or alkaline pancreatic secretions may be contributory.

D. ABNORMAL ESOPHAGEAL CLEARANCE

Acid refluxate normally is cleared and neutralized by esophageal peristalsis and salivary bicarbonate. During sleep, swallowing induced peristalsis is infrequent, prolonging acid exposure to the esophagus. One third of patients with severe gastroesophageal reflux disease also have diminished peristaltic clearance. Certain medical conditions such as scleroderma are associated with diminished peristalsis. Sjogren,s syndrome, anticholinergic medications, and oral radiation therapy may exacerbate gastroesophageal reflux disease due to impaired salivation.

Certain medical conditions such as scleroderma are associated with diminished peristalsis. Sjogrens syndrome, anticholinergic medications, and oral radiation therapy may exacerbate gastroesophageal reflux disease due to impaired salivation.

E. DELAYED GASTRIC EMPTYING

Impaired gastric emptying due to gastroparesis or partial gastric outlet obstruction potentiates gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Clinical Findings

A. SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

. Patients often report relief from taking antacids or baking soda. When this symptom is dominant, the diagnosis is established with a high degree of reliability. Many patients, however, have less specific dyspeptic symptoms with or without heartburn. Overall, a clinical diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux has a sensitivity of 80% but a specificity of only 70% . Severity is not correlated with the degree of tissue damage. In fact, some patients with severe esophagitis are only mildly symptomatic. Patients may complain of regurgitation the spontaneous reflux of sour or bitter gastric contents into the mouth. Less common symptoms include dysphagia, which may be due to abnormal peristalsis or the development of complications such as stricture or Barrett,s metaplasia.

Atypical manifestations of gastroesophageal disease are being recognized with increasing frequency. These include asthma, chronic cough, chronic laryngitis, sore throat, and noncardiac chest pain. Gastroesophageal Reflux may be either a causative or an exacerbating factor in up to 50% of these patients, especially those with refractory symptoms. Because many of these patients do not have heartburn or regurgitation, the diagnosis often is overlooked. Physical examination and laboratory data are normal in uncomplicated disease.

B. SPECIAL EXAMINATIONS

Uncomplicated patients with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation may be treated empirically for 4 weeks for gastroesophageal reflux disease without the need for diagnostic studies. Further investigation is required in patients with complicated disease and those unresponsive to empirical therapy.

1. Upper endoscopy Upper endoscopy with biopsy is the standard procedure for documenting the type and extent of tissue damage in gastroesophageal reflux. Fifty percent of patients with proved acid reflux will have visible mucosal abnormalities such as erythema and friability of the squamocolumnar junction and erosions, known as reflux esophagitis. However, endoscopy is normal in up to half of symptomatic patients and does not exclude mild disease. Esophageal abnormalities are graded on a scale of I (mild) to IV (severe erosions, stricture, or Barrett,s esophagus) . Initial medical therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease is guided by the presence of symptoms, not the endoscopic findings. Hence, endoscopy is not warranted for most patients with typical symptoms suggesting uncomplicated reflux disease. Endoscopy should be performed in patients whose symptoms have not responded after initial empirical therapy and patients with symptoms suggesting complicated disease (dysphagia, odynophagia, occult or overt bleeding, or iron deficiency anemia) . Endoscopy also may be warranted in patients with long standing symptoms (over 5 years) or patients

requiring continuous maintenance therapy, to look for Barrett,s esophagus.

2. Barium esophagography

This study plays a limited role. In patients with severe dysphagia, it is sometimes obtained prior to endoscopy to identify a stricture.

3. Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring Ambulatory pH monitoring is the best study for documenting acid reflux, but it is unnecessary in most patients. It is useful and indicated in the following situations: (1) to document abnormal esophageal acid exposure in a patient being considered for antireflux surgery who has a normal endoscopy (ie,no evidence of reflux esophagitis); (2) to evaluate patients with a normal endoscopy who have reflux symptoms unresponsive to therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (3) to detect either abnormal amounts of reflux or an association between reflux episodes and atypical symptoms such as noncardiac chest pain, asthma, chronic cough, laryngitis, and sore throat. It is recommended that most patients with atypical symptoms first be given an empirical trial of antireflux therapy with a high dose proton pump inhibitor for 2 -3 months. If symptoms fail to improve, a pH study is then performed

Differential Diagnosis

Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease may be similar to those of other diseases such as esophageal motility disorders, peptic ulcer, cholelithiasis, nonulcer dyspepsia, and angina pectoris. Reflux erosive esophagitis may be confused with pill induced damage, radiation esophagitis, or infections (CMV, herpes, Candida).

Complications

A. BRRETT`S ESOPHAGUS

This is a condition in which the squamous epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium containing goblet and columnar cells (specialized intestinal metaplasia). Present in up to 10% of patients with chronic reflux, it arises from

chronic reflux induced injury to the esophageal squamous epithelium. Barrett`s esophagus is suspected at endoscopy from the presence of orange, gastric type epithelium that extends upward from the stomach into the distal tubular esophagus in a tongue like or circumferential fashion. Biopsies obtained at endoscopy confirm the diagnosis. Three types of columnar epithelium may be identified: gastric cardiac, gastric fundic, and specialized intestinal metaplasia . Only the latter is believed to carry an increased risk of neoplasia.

Barrett`s esophagus does not provoke specific symptoms but gastroesophageal reflux does. Most patients have a long history of reflux symptoms, such as heartburn and regurgitation. Dysphagia due to impaired motility is common. Paradoxically, one third of patients report minimal or no symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, suggesting decreased acid sensitivity of Barrett`s epithelium. Indeed, over 90% of individuals with Barrett`s esophagus in the general population do not seek medical attention. Barrett`s esophagus may be complicated by stricture formation or acid peptic ulceration, which can bleed.

Barrett`s esophagus should be treated with long-term proton pump inhibitors. Surgical fundoplication may be desirable in some situations. Medical or surgical therapy may prevent progression, but there is no convincing evidence that regression occurs in most patients. Endoscopic ablation of Barrett`s epithelium with cautery probes or photosynthetic therapy(using photosensitizers and laser energy) has anecdotally resulted in partial or complete regression of columnar epithelium.

The most serious complication of Barrett`s esophagus is esophageal adenocarcinoma, which has an estimated annual incidence of 0.8 % , representing a 40 fold

risk compared with patients without Barrett`s esophagus. Virtually all adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and many such tumors of the gastric cardia arise from Barrett`s metaplasia. Thus, patients with Barrett`s esophagus who are operative candidates undergo endoscopic surveillance with mucosal biopsies every 2-3 years. Patients with low grade dysplasia are treated with aggressive medical management and endoscopic surveillance every 6-12 months. The management of high grade dysplasia is controversial. Since 30-40% may progress to (or already contain) invasive adenocarcinoma, surgery is usually recommended. Otherwise, photodynamic ablation or endoscopic mucosal resection may be considered.

Barrett`s epithelium of any length carries an increased risk of neoplasia. Although a clinical distinction is sometimes made between "short segment" (<3 cm length) and long segment Barrett`s esophagus, both warrant periodic endoscopic surveillance. Specialized intestinal metaplasia is present at the gastroesophageal junction in up to 20% of patients undergoing endoscopy in the absence of visible Barrett`s esophagus, but the significance of this entity is unclear.

B. PEPTIC STRICTURE

Stricture formation occurs in about 10% of patients with esophagitis. It is manifested by the gradual development of solid food dysphagia progressive over months to years. Often there is a reduction in heartburn because the stricture acts as a barrier to reflux. Most strictures are located at the gastroesophageal junction. Strictures located above this level usually occur with Barrett`s metaplasia. Endoscopy with biopsy is mandatory in all cases to

differentiate peptic structure from other benign or malignant causes of esophageal stricture ( Schatzki`s ring, esophageal carcinoma). Active erosive esophagitis is often present. Up to 90%of symptomatic patients are effectively treated with dilation. Dilation is continued over one to several sessions. A luminal diameter of 16-17 mm is usually sufficient to relieve dysphagia. Chronic therapy with a proton pump inhibitor ( Omeprazole or lansoprazole) is required to decrease the likelihood of stricture recurrence. Some patients require intermittent stricture dilation to maintain luminal patency, but operative management for strictures that do not respond to dilation is seldom required.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to provide symptomatic relief, to heal esophagitis ( if present ), and to prevent complications. In the majority of patients with uncomplicated disease, empirical treatment is initiated based upon a compatible history without the need for further confirmatory studies. Patients not responding and those with suspected complications undergo further evaluation with upper endoscopy or esophageal pH recording.

Patients with known erosive esophagitis, complications (such as a peptic stricture or Barrett,s esophagus), or suspected atypical manifestations (such as asthma or laryngitis) are treated initially with a proton pump inhibitor (see below). In most other patients, treatment may proceed in the following stepwise fashion.

1. Mild, intermittent symptoms -- Gastroesophageal Reflux is a lifelong disease that requires lifestyle modifications as well as medical intervention. The best advice is to avoid lying down within 3 hours after meals, the period of greatest reflux. Elevating the head of the bed on 6 inch blocks or a foam wedge to reduce reflux and enhance, especially for patients with nocturnal and typical symptoms. Patients should be advised to avoid acidic foods ( tomato products, citrus fruits, spicy foods, coffee) and agents that relax the lower esophageal sphincter or delay gastric emptying (fatty foods, peppermint, chocolate, alcohol, and smoking). Weight loss, avoidance of bending after meals, and reduction of meal size may also be helpful.

Antacids are the mainstay for rapid relief of occasional heartburn; however, their duration of action is less than 2 hours. Many are available over the counter. Those containing magnesium should not be used in renal failure, and patients with this condition should be cautioned appropriately. Gaviscon is an alginate antacid combination that decreases reflux in the upright position.

All H2 receptor antagonists are available in over the counter formulations: cimetidine 200 mg, ranitidine and nizatidine 75 mg, famotidine 10 mg all of which are half of the typical prescription strength. When taken for active heartburn, these agents have a delay in onset of at least 30 minutes; antacids provide more immediate relief. However, once these agents take effect, they provide heartburn relief for up to 8 hours. When taken before meals known to provoke heartburn, these agents reduce the symptom.

2. Moderate symptoms .......

Uncomplicated patients with typical reflux symptoms that occur several Times per week or daily should be treated empirically with an H2 receptor antagonist. Standard prescription doses of these agents are ranitidine or nizatidine 150 mg, famotidine 20 mg, or cimetidine 400 - 800 mg, twice daily. These agents reduce 24 hour acidity by over 60% . Ranitidine and cimetidine are available in less expensive generic formulations. Treatment twice daily affords improvement in up to two - thirds of patients. Given their superior efficacy and once daily dosing, proton pump inhibitors increasingly are prescribed as first line therapy for mild to moderate symptoms in preference to beginning with an H2 receptor antagonists are significantly less expensive symptomatic relief in most patients with mild to moderate reflux symptoms.

For patients whose symptoms persist despite 6 weeks of standard doses of H2 receptor antagonist therapy, continued therapy or an increase in dosage of H2 receptor antagonists is seldom effective in providing symptom relief. These patients should be treated with a proton pump inhibitor (Omeprazole or rabeprazole 20mg, lansoprazole 30mg, or esomeprazole or pantoprazole 40mg or (Dexlansoprazole 30mg, 60mg which is the most recent PPI) once daily, Doxirazol is the 1st and only dexlansoprazole in Egypt. The decision to prescribe proton pump inhibitors is based upon the presence of persistent symptoms, not endoscopic findings.

In those who achieve good symptom relief with either an H2 receptor antagonist or a proton pump inhibitor, therapy should be discontinued after 8-12 weeks. Patients whose symptoms relapse may be treated with either continuous or intermittent courses of therapy depending upon symptom frequency and patient preference. Many patients are controlled adequately with intermittent courses of therapy rather than continuous maintenance treatment.

Promotility drugs (metoclopramide, cisapride, bethanechol) reduce reflux by increasing lower esophageal sphincter pressure and enhancing esophageal peristalsis and gastric emptying. Side effects preclude the use of these agents for reflux disease. Cisapride causes QT prolongation, leading to serious cardiac arrhythmias, and has been withdrawn from the market in the United states. Metoclopramide is a dopamine antagonist that may cause neuropsychiatric side effects in up to one-third of patients, limiting it to short term use only.

3. Severe symptoms and erosive

disease .....

For patients with severe symptoms and for patients who undergo endoscopy and have documented erosive esophagitis, the optimal initial therapy is a proton pump inhibitor (Omeprazole or rabeprazole 20mg, lansoprazole 30mg, pantoprazole or esomeprazole 40mg) once daily. Proton pump inhibitors given once daily provide symptom relief and healing of esophagitis in over 80% and given twice daily provide relief in over 95% of patients compared with under 50% with standard doses of H2 receptor antagonists and are therefore the drugs of choice for severe or erosive disease. Because there appears to be little difference between these agents in efficacy or side effect profiles, the choice of agent is determined by cost. Esomeprazole, the S-isomer of Omeprazole, provides slightly greater inhibition of 24 hour gastric acidity than the other agents, resulting in a small (5%) therapeutic advantage over Omeprazole. Approximately 10 -20% of patients fail to achieve symptom relief with a once daily dose within 2- 4 weeks and require a higher dosage (twice daily) proton pump inhibitor. Therefore some recommend initiating therapy with a twice daily dose of proton pump inhibitor, reducing therapy after 2 -4 weeks to a once daily dose. The initial course of therapy is usually 8 - 12 weeks. As tissue healing correlates well with symptom resolution, repeat endoscopy is warranted in patients only if they fail to respond to once daily or twice daily proton pump inhibitor therapy.

After discontinuation of proton pump inhibitor therapy, relapse of symptoms occurs in 80% of patients within 1 year the majority of relapses occurring within the first 3 months. Therefore, chronic therapy to maintain symptom remission is required in most but not all patients. Patients with severe erosive esophagitis, Barrett`s esophagus, or peptic stricture should be maintained on chronic therapy with a proton pump inhibitor at a dose sufficient to provide complete symptom relief. In other patients a trial off proton pump inhibitors should be considered. Patients with prolonged symptomatic remissions (over 3 months) may be treated effectively with intermittent 4 to 8 week courses of acute proton pump inhibitor therapy. Patients with prompt recurrence of symptoms ( within 3 months ) require chronic maintenance therapy with either a proton pump inhibitor or an H2 receptor antagonist. The therapy should be stepped down to the lowest dose that is effective in controlling reflux symptoms.

The maintenance doses of proton pump inhibitors may escalate over time, with over 20% of patients eventually requiring double or triple doses of proton pump inhibitors to control symptoms.

4. Extraesophageal reflux manifestations----- Establishing a causal relationship between gastroesophageal reflux and Extraesophageal symptoms (eg, asthma, hoarseness, cough ) can be difficult. Although ambulatory esophageal pH testing can document the presence of increased acid esophageal reflux, it does not prove a causative connection. A trial of a twice daily proton pump inhibitor for 2 - 3 months helps determine whether these symptoms improve after acid suppression.

5. Unresponsive disease..... Approximately 10 - 20% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms do not respond to once daily doses of proton pump inhibitors, and 5% do not respond to twice daily doses. These patients undergo endoscopy prior to escalation of therapy. Patients without endoscopically visible esophagitis should undergo esophageal pH monitoring to determine the amount of esophageal acid reflux and to assess whether the refractory symptoms are truly acid related. The presence of active erosive esophagitis usually is indicative of inadequate acid suppression and can almost always be treated successfully with higher proton pump inhibitor doses (eg, Omeprazole 40mg twice daily). Breakthrough acid production appears to occur at night in patients with severe disease. A twice daily proton pump inhibitor (before breakfast and dinner) and a bedtime dose of an H2 receptor antagonist may be more effective(and less expensive) in controlling nocturnal acid than a proton pump inhibitor given three times daily. Truly refractory esophagitis may be caused by gastrinoma with gastric acid hypersecretion (Zollinger -Ellison syndrome), pill induced esophagitis, resistance to proton pump inhibitors, and medical noncompliance.

B. SURGICAL TREATMENT

Surgical fundoplication affords good to excellent relief of symptoms and healing of esophagitis in over 85% of properly selected patients and may now be performed laparoscopically with low complication rates in most instances. Cost effectiveness studies suggest that aggregate medical costs exceed surgical costs

Approximately 10 - 20% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms do not respond to once daily doses of proton pump inhibitors, and 5% do not respond to twice daily

after 10 years. The longevity of the beneficial effects of fundoplication are debated. Different surgical centers report 10 year success rates ranging from 60%to 90% . However, over half of patients require continued acid suppression medication after fundoplication. Further more, over 30% of patients develop new symptoms of dysphagia, bloating, increased flatulence, or dyspepsia. Surgical treatment is not recommended for patients who are well controlled with medical therapies but should be considered (1) for otherwise healthy patients with Extraesophageal manifestations of reflux, as these symptoms often require high doses of proton pump inhibitors and may be more effectively controlled with antireflux surgery (2) for those with severe reflux disease who are unwilling to accept lifelong medical therapy due to its expense, inconvenience, or theoretical risks and (3) for patients with erosive disease who are intolerant of or resistant to proton pump inhibitors

C. ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

There are two endoscopic devices for the treatment of mild to moderate gastroesophageal reflux disease. The first uses an endoscopic "sewing machine" to place sutures below the gastroesophageal junction in the region of the gastric cardia, creating a mucosal plication that may mimic a surgical fundoplication. The second employs an intraesophageal balloon catheter from which needle electrodes are inserted through the mucosa and into the muscularis at multiple levels of the distal esophagus and cardia, permitting application of radiofrequency wave current. It is believed that this current may disrupt neural reflux pathway from the stomach to the esophagus, resulting in a decrease in relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter. Reports of success come from uncontrolled studies routine use is not yet advised.

REFERENCES

1 - ELL C et al: Endoscopic mucosal resection of early cancer and high grade dysplasia in Barrett"s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2000 ; 118:670. [Should be considered as alternative to esophageal resection in selected patients.]

2 - Extraesophageal presentations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;No. 8, Supplement.

3 - Fass R et al: Nonerosive reflux disease. current concepts and dilemmas. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:303.

4 - Filipi C et al: Transoral, flexible endoscopic suturing for the treatment of GERD: a multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endoscopic 2001;53:416.

5 - Gerson L et al: A cost effectiveness analysis of prescribing strategies in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:395. 6 - Inadomi J et al: Step down management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2001;121:1095.

7 - Klinkenberg-Knol EC et al: Long term omeprazole treatment in resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease : efficacy, safety, and influence on gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology 2000;118:661 .

8 - Sampliner R et al: Effective and safe endoscopic reversal of nondysplastic Barrett"s esophagus with thermal electrocoagulation combined with high dose acid inhibition: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endoscopic 2001;53:554.

9 · Schnell T et al: Long term nonsurgical management of Barrett"s esophagus with high grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1607.

10 - Sharma P : Short segment Barrett esophagus and specialized columnar mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:331.

11 - Spechler S et al: Long term outcomes of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease. JAMA 2001;285:2331.

12 - Triadifilopolous G et al: Radiofrequency energy delivery to the gastroesophageal junction for the treatment of GERD. Gastrointest Endoscopic 2001;53:407.

13 - Weston A et al: Long term follow up of Barrett"s high grade dysplasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1888

info@utopiapharma.com

info@utopiapharma.com

Plot No. (2) Industrial Zone (A7) - formerly Zizinia - Cairo - Ismailia Road - 10th of Ramadan - Sharkia

Plot No. (2) Industrial Zone (A7) - formerly Zizinia - Cairo - Ismailia Road - 10th of Ramadan - Sharkia